Market structures provide a starting point for assessing economic environments in business. An understanding of how companies and markets work allows business professionals and leaders to accurately judge industry and market news, policy changes and legislation and how the economy shapes important decisions.

What Are Market Structures?

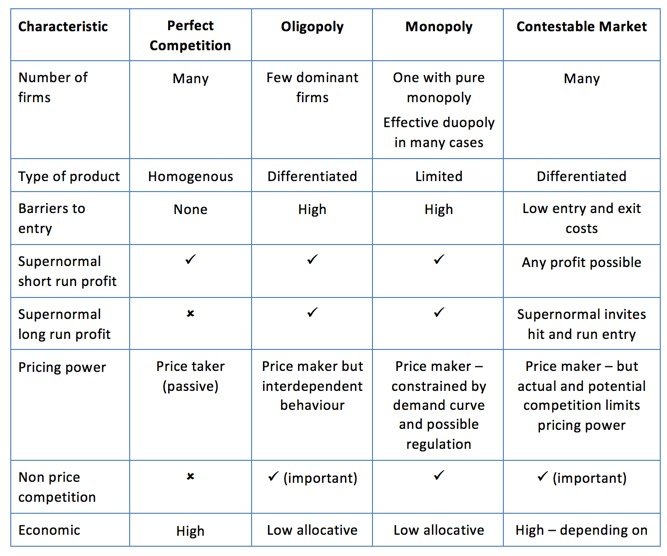

“Market structures” refer to the different market characteristics that determine relations between sellers to each other, of sellers to buyers and more. There are several basic defining characteristics of a market structure, such as the following:

- The commodity or item that’s sold and the extent of production differentiation.

- The ease or difficulty of entering and exiting the market.

- The distribution of market share for the largest firms.

- The number of companies in the market.

- The number of buyers and how they work with or against the sellers to dictate price and quantity.

- The relationship between sellers.

Types of Market Structures

There are four basic types of market structures.

Pure Competition

Pure or perfect competition is a market structure defined by a large number of small firms competing against each other. A single firm doesn’t have significant marketing power, and as a result, the industry produces an optimal level of output because firms don’t have the ability to influence market prices. Supply and demand determine the amount of goods and services produced, along with the market prices set by the companies in the market. Products are identical to competitors’ products, and there are no significant barriers to entering and exiting the market.

The pure competition market structure is rare in the real world. This is a theoretical model that is helpful when looking at industries with similar characteristics. In other words, it’s a good reference point for other market structures. The best examples of pure competition market structures are stock, agricultural and craft markets.

Monopolistic Competition

Like pure competition, monopolistic competition is a market structure referring to a large number of small firms competing against each other. However, firms in monopolistic competition sell similar but highly differentiated products. Lowest possible cost production, which leads to optimal output in a pure competition market structure, is not assumed.

These factors give firms in a monopolistic competition market power to charge higher prices within a certain range. The products are remarkably similar, but small differences become the basis for firms’ marketing and advertising. Differentiation can include style, brand name, location, packaging, advertisement, pricing strategies and more.

Examples include fast food restaurants, clothing stores, breakfast cereal companies, service and repair markets, tutoring companies and beauty salons and spas. Products and services at a beauty salon are quite similar, but these companies will use certain value propositions, such as quality of services and appealing pricing, to draw more customers. They may even advertise brand-name beauty products that are themselves in monopolistic competition; there is little that separates makeup and hair products, as far as what constitutes these products and their use.

Producers freely enter the market when profits are attractive. There is easy entry and exit in monopolistic competition.

Oligopoly

An oligopoly is dominated by a few firms, resulting in limited competition. They can collaborate with or compete against each other to use their collective market power to drive up prices and earn more profit.

Entering into an oligopoly is difficult. The most powerful companies have control over raw materials, patents and financial and physical resources that create barriers for potential entries. This is what helps set high prices. However, if prices are too high, buyers will head to product substitutes in the market.

Products may be homogeneous or differentiated. Typically, there are three to five dominant firms, but this number can vary depending on the market. For instance, video gaming consoles are an oligopoly with three companies Microsoft, Sony and Nintendo dominating the market. Other examples of oligopolies are the automobile and gasoline industries.

Pricing, profits and production levels change as the dynamic relationship between sellers and buyers changes.

Pure Monopoly

A monopoly exists when there’s a single firm that controls the entire market. The firm and industry are synonymous. This firm is the sole producer of a product, and there are no close substitutes. Because there are no alternatives, the firm has the highest level of market power. Hence, monopolists often reduce output, increase prices and earn more profit.

Entry or exit is blocked in a pure monopoly. This can occur for more than one reason, as seen in two of the best examples for pure monopolies: public utilities and professional sports leagues.

Public utilities are considered natural monopolies because they have economies of scale a firm receives certain cost advantages due to its size — in an extreme way. New firms cannot start up because it would be incredibly expensive to reach scale in a short amount of time. Building a maze of pipes and wires to be able to compete with the firm would require a lot of capital, and there would be legal barriers to entry. That’s why there are typically government monopolies (or government regulations) for natural monopolies.

Professional sports leagues control player contracts and have leases on major city stadiums and arenas. It would take a substantial amount of capital to lure away top talent and secure a large enough place to showcase that talent, if someone wanted to start a professional sports league. Plus, there are broadcasting rights and more at play. For example, for the 2017-2018 season, 37 players in the NBA will earn $20 million or more in salary alone. New arenas in the league cost in the neighborhood of $500 million. Television rights for the NBA were extended in February 2016 with ESPN and TNT for a value of about $2.66 billion per year.

The most important features of market structure are:

- The number of firms (including the scale and extent of foreign competition)

- The market share of the largest firms (measured by the concentration ratio – see below)

- The nature of costs (including the potential for firms to exploit economies of scale and also the presence of sunk costs which affects market contestability in the long term)

- The degree to which the industry is vertically integrated – vertical integration explains the process by which different stages in production and distribution of a product are under the ownership and control of a single enterprise. A good example of vertical integration is the oil industry, where the major oil companies own the rights to extract from oilfields, they run a fleet of tankers, operate refineries and have control of sales at their own filling stations.

- The extent of product differentiation (which affects cross-price elasticity of demand)

- The structure of buyers in the industry (including the possibility of monopsony power)

- The turnover of customers (sometimes known as “market churn”) – i.e. how many customers are prepared to switch their supplier over a given time period when market conditions change. The rate of customer churn is affected by the degree of consumer or brand loyalty and the influence of persuasive advertising and marketing

Pricing Decisions

Determinants of Price Under Perfect Competition

Market price is determined by the equilibrium between demand and supply in a market period or very short run. The market period is a period in which the maximum that can be supplied is limited by the existing stock. The market period is so short that more cannot be produced in response to increased demand. The firms can sell only what they have already produced. This market period may be an hour, a day or a few days or even a few weeks depending upon the nature of the product.

Market Price of a Perishable Commodity

In the case of perishable commodity like fish, the supply is limited by the available quantity on that day. It cannot be stored for the next market period and therefore the whole of it must be sold away on the same day whatever the price may be.

Market Price of Non-Perishable and Reproducible Goods

In case of non-perishable but reproducible goods, some of the goods can be preserved or kept back from the market and carried over to the next market period. There will then be two critical price levels.

The first, if price is very high the seller will be prepared to sell the whole stock. The second level is set by a low price at which the seller would not sell any amount in the present market period, but will hold back the whole stock for some better time. The price below which the seller will refuse to sell is called the Reserve Price.